Editor's Note: This post is the first in a two-part series exploring the current state, challenges, and progress being made in pursuit of the world-class city.

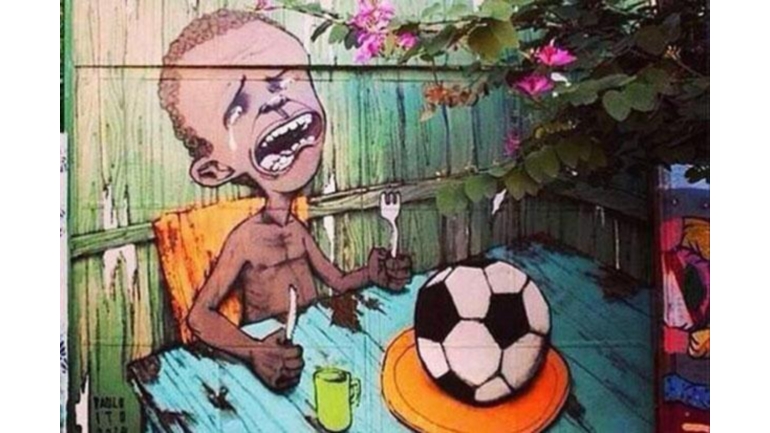

On Brazil’s city walls, it is not uncommon to see “F#*K FIFA” [my own censorship] or illustrations of malnourished children begging for food from fat politicians and World Cup representatives.

Such social commentary centered on the 20th FIFA (Fédération Internationale de Football Association) World Cup hosted by Brazil is unexpected in the football capital of the world. Football is the pride of Brazil, a country that has won the World Cup more than any other country.

An example of the Brazilian graffiti about the 2014 World Cup. Source: carlosdorna imgur.com

While the Brazilian government speaks of the legacy gained from hosting the World Cup, its citizens use the walls and streets of their cities to question 'at what cost?'

The football spirit of Brazil was deflated long before the country lost to Germany this year. Many Brazilians argue that the cost of event preparations, currently estimated at $11 billion, should have been spent on education, housing and food assistance for its citizens rather than large stadiums, surveillance and venues for a four-week event.

This concern for citizen welfare is supported by Brazil’s poverty rate. Brazil is the seventh largest economy, but one of the most economically unequal countries in the world.

Another point of tension is the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Brazilians in favela communities built on public land to make way for the stadiums, parking lots and other event accommodations. Despite the progressive policy of the City Statute that protects the existence of these communities, the World Cup created opportunities for the suspension of squatter rights in Brazil. [i]

It is ironic that the poor, the favelados evicted from the only homes they can afford cannot afford the ticket price of football games played on the land they once called home. Their role in this international event is to build the stadiums and serve the tourists. The same occurred in South Africa four years ago during World Cup preparations. [ii]

The voices of descent and apathy toward the recent World Cup give rise to a broader discussion of urban development: the world-class city, which is creating deep inequalities in city life.

The Making of an Unequal World-Class City

Current urban inequalities, such as those discussed above, are described by University of California, Berkeley Professor Ananya Roy in her TEDCity2.0 2013 talk about the future of urbanism: the world-class city.

Professor Roy describes the world-class city as the current blueprint of urban development undertaken by governments to attract foreign investment and achieve global competitiveness.

Within this framework, towers of glass and steel, large airports with luxury accommodations, and sporting events that show ingenuity through the creation of billion-dollar venues with state of the art transportation and urban centers become the standard of every city. The discussion around the world-class city is important because cities are our global future.

The world is relocating to cities at a faster rate than ever before, and the majority of population growth will happen in urban regions. It is estimated that the urban population of the developing world will reach 4 billion in less than ten years. Where will this growing population live? Not in the world-class city. [iii]

Professor Roy explains that the paradox of the world-class city lies in its dirty little secret - its dependency of the poor, the urban majority that the world-class city excludes from its existence.

The poor clean the homes and offices, work within the factories, raise and teach the children of the world class city; in other words, the poor maintain and build the world-class city life for the minority, but not for themselves.

In the world-class city, the poor are pushed to the margins. Slum, informal settlement, barrio, favela, colonias, gecekondus and bustee are all used to describe the same “...refuge for people displaced by erosions, cyclones, floods, famine, or that more recent generator of insecurity, development.” [iv]

Despite this reliance, the loyalty of city governments lies with the standards set by development practitioners and foreigner investors to build a city of international importance. In Brazil, this comes in the form of hosting world-class sporting events, such as the 20th FIFA World Cup and the 2016 Summer Olympics, no matter the impact to its citizens or use of public funds.

The once Brazilian president, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, speaks to this truth. When Brazil was awarded the bid for the 20th World Cup, he said with tears in his eyes,

“...Today is the day that Brazil gained its international citizenship...I think this is the day to celebrate because Brazil has left behind the level of second-class countries and entered the rank of first-class countries. Today, we earned respect. The world has finally recognized that this is Brazil’s time.”

Unfortunately, the respect and citizenship discussed above are not extended to the poor in the world-class cities of Brazil or any other country. This is especially unfortunate in Brazil since the constitution of Brazil upholds the "Right to the City" for all. [v]

Despite state and corporate support for the current evolution of the world-class city, Professor Roy points out that its story does not end here; it is only the beginning. I sat down with Professor Roy to discuss her TED talk and learn how urban civil society is unmaking and remaking the world-class city.

Please note that my conversation with Professor Roy will be shared in a second post, "A Conversation with Ananya Roy: The Unmaking and Remaking of the World-Class City through Solidarity, Visibility and Dwelling."

References for Blog Post:

[i, ii, v] Zirin, Dave. Brazil’s Dance with the Devil: The World Cup, The Olympics and the Fight for Democracy. Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2014.

[iii, iv] Davis, Mike. Planet of Slums. New York: Verso, 2007.